Origins and Traditions

In a private club in Tokyo's neon-lit Ginza entertainment district, men in dark pinstripe suits drink, smoke and play cards. A few of the men are huddled together in a corner, involved in hushed but animated conversation. Others puff their chests out for the accommodating "comfort women" who adorn the smoke-filled room like well-placed flower arrangements.

In a private club in Tokyo's neon-lit Ginza entertainment district, men in dark pinstripe suits drink, smoke and play cards. A few of the men are huddled together in a corner, involved in hushed but animated conversation. Others puff their chests out for the accommodating "comfort women" who adorn the smoke-filled room like well-placed flower arrangements.

The club is on the second floor of a small building where the constant whir and clang of a busy pachinko parlor on the ground floor can be heard upstairs. Pachinko is the Japanese national obsession, a slot machine that sends tiny chrome balls through a vertical maze, like a pinball machine set on end but smaller in size. The relentless chatter of hundreds of moving pachinko balls is softened by the club's sound system, which plays the theme from The Godfather, performed on traditional Japanese instruments, koto (Japanese banjo) and wood flute.

A squat older man sits toward the back of the room at a table surrounded by bowing young associates, who respond to every order and request he makes with an unvarying hail of "Hai! Hai!" ("Yes! Yes!"). The older man is flanked by two women—one in a short black cocktail dress, the other in a schoolgirl's pleated plaid skirt and white blouse. Both women cover their mouths and giggle at the man's every gruff word.

A young man in a shiny sharkskin suit enters the room, his head bowed. The other men immediately take notice and stop talking. The young man approaches the older man's table. He does not dare lift his eyes. Without a word he formally presents an artfully wrapped object to the older man. The package is no bigger than a small piece of candy, but the young man sets it down on the table ceremoniously with both hands. His left pinky is heavily bandaged. The old man stares at the offering, then stares at the young man's damaged hand. The moment is tense until the older man nods, his face relaxing a bit, and orders one of his minions to remove the offering without opening it. Everyone in the room knows what it is, the severed last joint of the young man's finger. The gift is an act of appeasement. Several men in the room have also lost parts of their pinkies. It is one of the telltale signs of the Japanese yakuza.

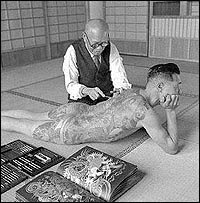

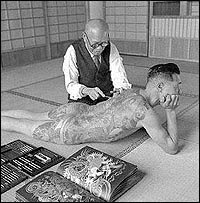

Yakuza members also favor tattoos, but theirs are elaborate body murals that often cover the entire torso, front and back, as well the arms to below the elbow and the legs to mid-calf. Naked, a fully tattooed yakuza looks like he's wearing long underwear. Dragons, flowers, mountainous landscapes, turbulent seascapes, gang insignias and abstract designs are typical images used for yakuza body art. The application of these extensive tattoos is painful and can take hundreds of hours, but the process is considered a test of a man's mettle.

Yakuza members also favor tattoos, but theirs are elaborate body murals that often cover the entire torso, front and back, as well the arms to below the elbow and the legs to mid-calf. Naked, a fully tattooed yakuza looks like he's wearing long underwear. Dragons, flowers, mountainous landscapes, turbulent seascapes, gang insignias and abstract designs are typical images used for yakuza body art. The application of these extensive tattoos is painful and can take hundreds of hours, but the process is considered a test of a man's mettle.

To a Westerner's eye, the yakuza's 1950s rat-pack style of dress can seem comically retro. Shiny tight-fitting suits, pointy-toed shoes and longish pomaded hair—long out of style in America—are commonplace among the yakuza today. They also favor large flashy American cars, like Cadillacs and Lincolns. Unlike other organized crime groups around the world, the yakuza have no interest in keeping a low profile. In fact, in most Japanese cities, yakuza social clubs and gang headquarters are clearly marked with signs and logos prominently displayed.

In a private club in Tokyo's neon-lit Ginza entertainment district, men in dark pinstripe suits drink, smoke and play cards. A few of the men are huddled together in a corner, involved in hushed but animated conversation. Others puff their chests out for the accommodating "comfort women" who adorn the smoke-filled room like well-placed flower arrangements.

In a private club in Tokyo's neon-lit Ginza entertainment district, men in dark pinstripe suits drink, smoke and play cards. A few of the men are huddled together in a corner, involved in hushed but animated conversation. Others puff their chests out for the accommodating "comfort women" who adorn the smoke-filled room like well-placed flower arrangements.The club is on the second floor of a small building where the constant whir and clang of a busy pachinko parlor on the ground floor can be heard upstairs. Pachinko is the Japanese national obsession, a slot machine that sends tiny chrome balls through a vertical maze, like a pinball machine set on end but smaller in size. The relentless chatter of hundreds of moving pachinko balls is softened by the club's sound system, which plays the theme from The Godfather, performed on traditional Japanese instruments, koto (Japanese banjo) and wood flute.

A squat older man sits toward the back of the room at a table surrounded by bowing young associates, who respond to every order and request he makes with an unvarying hail of "Hai! Hai!" ("Yes! Yes!"). The older man is flanked by two women—one in a short black cocktail dress, the other in a schoolgirl's pleated plaid skirt and white blouse. Both women cover their mouths and giggle at the man's every gruff word.

A young man in a shiny sharkskin suit enters the room, his head bowed. The other men immediately take notice and stop talking. The young man approaches the older man's table. He does not dare lift his eyes. Without a word he formally presents an artfully wrapped object to the older man. The package is no bigger than a small piece of candy, but the young man sets it down on the table ceremoniously with both hands. His left pinky is heavily bandaged. The old man stares at the offering, then stares at the young man's damaged hand. The moment is tense until the older man nods, his face relaxing a bit, and orders one of his minions to remove the offering without opening it. Everyone in the room knows what it is, the severed last joint of the young man's finger. The gift is an act of appeasement. Several men in the room have also lost parts of their pinkies. It is one of the telltale signs of the Japanese yakuza.

Yakuza members also favor tattoos, but theirs are elaborate body murals that often cover the entire torso, front and back, as well the arms to below the elbow and the legs to mid-calf. Naked, a fully tattooed yakuza looks like he's wearing long underwear. Dragons, flowers, mountainous landscapes, turbulent seascapes, gang insignias and abstract designs are typical images used for yakuza body art. The application of these extensive tattoos is painful and can take hundreds of hours, but the process is considered a test of a man's mettle.

Yakuza members also favor tattoos, but theirs are elaborate body murals that often cover the entire torso, front and back, as well the arms to below the elbow and the legs to mid-calf. Naked, a fully tattooed yakuza looks like he's wearing long underwear. Dragons, flowers, mountainous landscapes, turbulent seascapes, gang insignias and abstract designs are typical images used for yakuza body art. The application of these extensive tattoos is painful and can take hundreds of hours, but the process is considered a test of a man's mettle.To a Westerner's eye, the yakuza's 1950s rat-pack style of dress can seem comically retro. Shiny tight-fitting suits, pointy-toed shoes and longish pomaded hair—long out of style in America—are commonplace among the yakuza today. They also favor large flashy American cars, like Cadillacs and Lincolns. Unlike other organized crime groups around the world, the yakuza have no interest in keeping a low profile. In fact, in most Japanese cities, yakuza social clubs and gang headquarters are clearly marked with signs and logos prominently displayed.

But despite their garish style, the yakuza cannot be taken lightly. In Japan there are 110,000 active members divided into 2,500 families. By contrast, the United States has more than double the population of Japan but only 20,000 organized crime members total, and that number includes all criminal organizations, not just the Italian-American Mafia. The yakuza's influence is more pervasive and more accepted within Japanese society than organized crime is in America, and the yakuza have a firm and long-standing political alliance with Japan's right-wing nationalists. In addition to the typical vice crimes associated with organized crime everywhere, the yakuza are well ensconced in the corporate world. Their influence extends beyond Japanese borders and into other Asian countries, and even into the United States.

Oyabun-Kobun, Father-Child

Like the Mafia, the yakuza power structure is a pyramid with a patriarch on top and loyal underlings of various rank below him. The Mafia hierarchy is relatively simple. The capo (boss) rules the family with the assistance of his underboss and consigliere (counselor). On the next level, captains run crews of soldiers who all have associates (men who have not been officially inducted into the Mafia) to do their bidding.

Like the Mafia, the yakuza power structure is a pyramid with a patriarch on top and loyal underlings of various rank below him. The Mafia hierarchy is relatively simple. The capo (boss) rules the family with the assistance of his underboss and consigliere (counselor). On the next level, captains run crews of soldiers who all have associates (men who have not been officially inducted into the Mafia) to do their bidding.The yakuza system is similar but more intricate. The guiding principle of the yakuza structure is the oyabun-kobun relationship. Oyabun literally means "father role"; kobun means "child role." When a man is accepted into the yakuza, he must accept this relationship. He must promise unquestioning loyalty and obedience to his boss. The oyabun, like any good father, is obliged to provide protection and good counsel to his children. However, as the old Japanese saying states, "If your boss says the passing crow is white, then you must agree." As the yakuza put it, a kobun must be willing to be a teppodama (bullet) for his oyabun.

The levels of management within the yakuza structure are much more complex than the Mafia's. Immediately under the kumicho (supreme boss) are the saiko komon (senior adviser) and the so-honbucho (headquarters chief). The wakagashira (number-two man) is a regional boss responsible for governing many gangs; he is assisted by the fuku-honbucho, who is responsible for several gangs of his own. A lesser regional boss is a shateigashira, and he commonly has a shateigashira-hosa to assist him. A typical yakuza crime family will also have dozens of shatei (younger brothers) and many wakashu (junior leaders).

A successful candidate for admission into the Mafia must participate in a ceremony where his trigger finger is pricked and the blood smeared on the picture of a saint, which is then set on fire and must burn in the initiate's hands as he swears his loyalty to the family. In the yakuza initiation ceremony, the blood is symbolized by sake (rice wine). The oyabun and the initiate sit face-to-face as their sake is prepared by azukarinin (guarantors). The sake is mixed with salt and fish scales, then carefully poured into cups. The oyabun's cup is filled to the brim, befitting his status; the initiate gets much less. They drink a bit, then exchange cups, and each drinks from the other's cup. The kobun has then sealed his commitment to the family. From that moment on, even the kobun's wife and children must take a backseat to his obligations to his yakuza family.